Endometriosis

Understanding Endometriosis

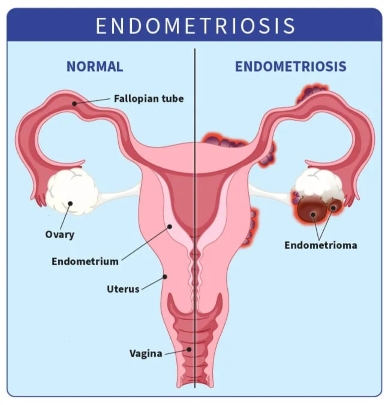

Endometriosis is a long-lasting health issue where cells resembling those that line the inside of the womb grow in other places within the body. These cells follow the same monthly pattern as the womb lining — they build up and try to shed — but since they’re trapped, this causes swelling, soreness, and the formation of scar tissue or sticky bands between organs.

The growths are most often found around the pelvis, on surfaces covering the organs, the ovaries, tubes, intestines, or urinary bladder. In less common situations, they can appear farther away, such as in scar tissue from surgery or even in the chest cavity.

Around one in ten people who menstruate experience this condition during their reproductive years, though its effects can continue afterward. It touches millions worldwide, across every background and community.

Another related problem is adenomyosis, where these same kinds of cells grow into the muscular wall of the womb itself, often leading to particularly heavy and uncomfortable monthly bleeding. Many people have both conditions together.

Different Forms of Endometriosis

Doctors classify the condition into four main forms depending on where the tissue appears and how deeply it invades. It’s common for someone to have a combination:

• Surface-level peritoneal — thin patches on the lining inside the pelvis

• Ovarian cysts (endometriomas) — dark-fluid-filled sacs on the ovaries, sometimes called chocolate cysts

• Deeply invading — growths that reach further into tissues, often involving the intestines, bladder, or area behind the womb

• Outside the pelvis — unusual locations beyond the lower abdomen, like the lungs or old surgical scars

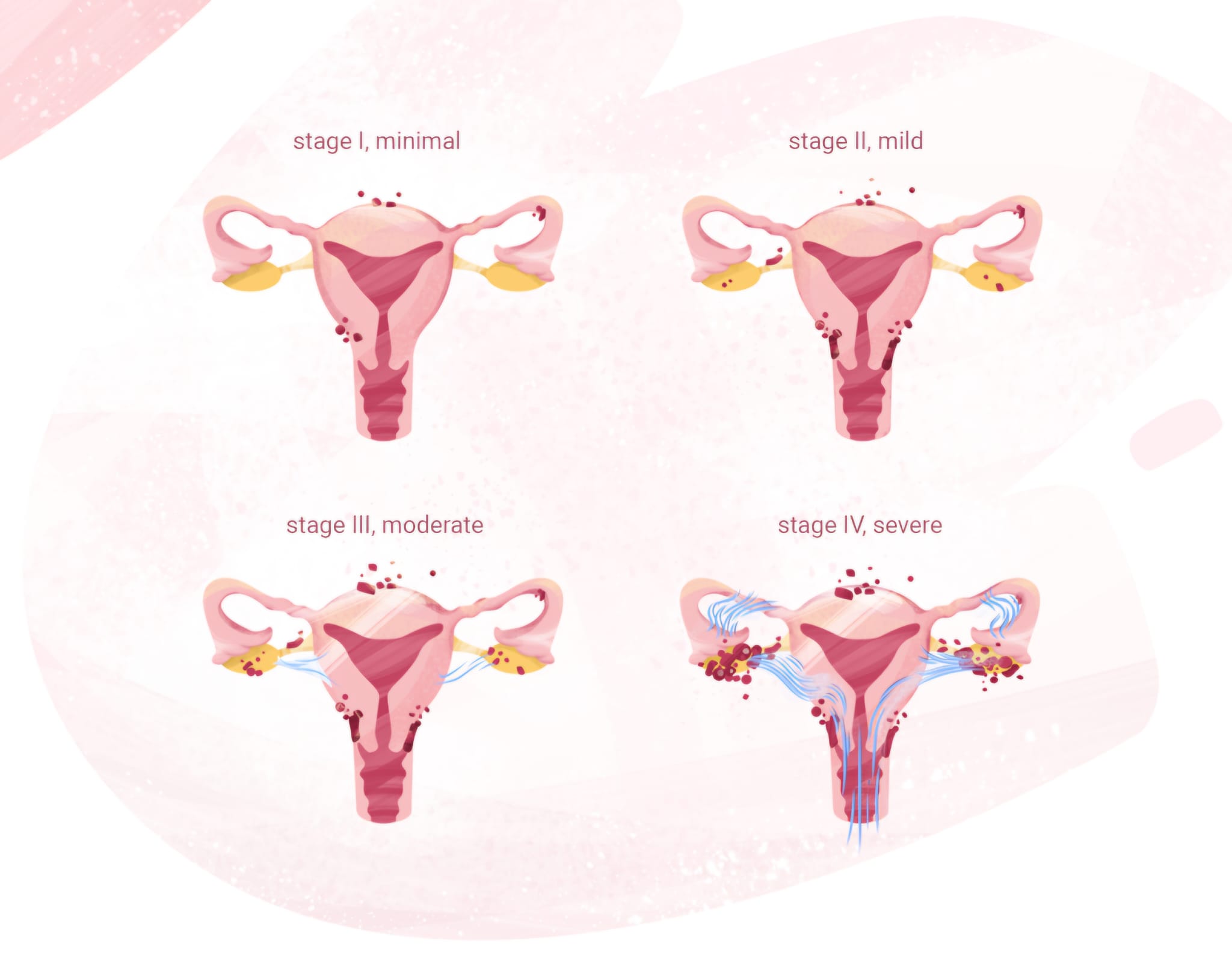

Endometriosis Stages

Endometriosis stages range from I (minimal) to IV (severe), with higher point scores indicating more extensive disease. Importantly, the stage reflects the physical extent of the disease seen during surgery (usually laparoscopy), not the severity of symptoms. Many people with Stage I experience intense pain, while some with Stage IV have milder symptoms.

Stage I: Minimal Endometriosis

This is the least extensive form. There are only a few small, superficial implants, typically on the peritoneum (the lining of the abdominal cavity) or ovaries. Adhesions are rare or absent, and there are no significant cysts.

Often mild or even no symptoms at all, though some experience painful periods or pelvic discomfort.

Stage II: Mild Endometriosis

More implants than Stage I, and they tend to be deeper. Light adhesions may begin forming, but the disease remains relatively limited without large cysts.

Common locations of the adhesions: Peritoneum, ovaries, and possibly fallopian tubes.

Stage III: Moderate Endometriosis

The disease is more widespread with numerous deep implants. Small endometriomas appear on one or both ovaries, and filmy adhesions can start to connect organs.

Key feature — Ovarian "chocolate cysts" (endometriomas), which contain thick, old blood.

More deep symptoms: strong chronic pelvic pain, heavy periods, bowel/bladder issues, increased infertility risk.

Often the management of symptoms involves laparoscopic excision of implants and cysts, hormonal suppression, or fertility support like IVF.

Stage IV: Severe Endometriosis

The most advanced stage, with extensive deep implants, large endometriomas on one or both ovaries, and dense adhesions that can distort or "freeze" pelvic organs. Disease may extend to bowels, bladder, or rarely beyond the pelvis.

Symptoms: Debilitating pain, severe menstrual cramps, gastrointestinal problems, urinary issues, and significant infertility challenges.

The management of illness usually involves a complex surgery by endometriosis specialists (possibly involving multiple disciplines), long-term hormonal therapy, pain management strategies, and often assisted reproduction.

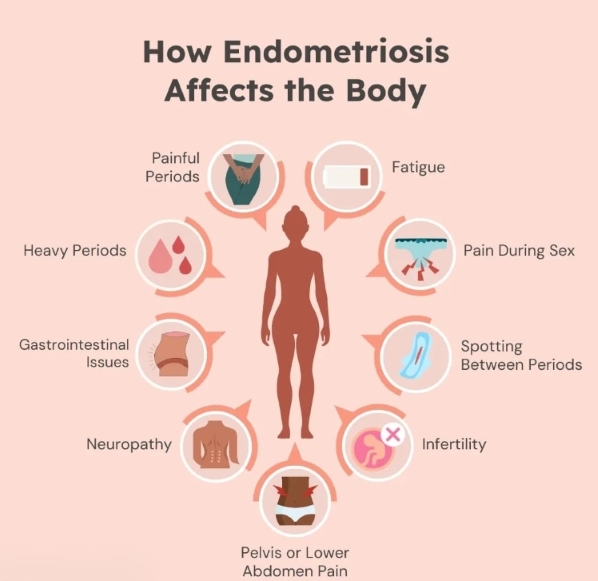

How Endometriosis Can Feel

Everyone’s experience is different. Some face intense challenges, while others notice very little. The strength of symptoms doesn’t always reflect how much tissue is present or where it is. Many of these signs can also appear with other illnesses, so it’s worth talking to a healthcare professional if they affect your daily routine.

Soreness — the hallmark experience

A deep, persistent ache in the lower abdomen is frequently reported, sometimes feeling like sharp stabs or heavy pressure that spreads to the back or legs. This often becomes far worse in the days leading up to and during menstruation. For many, monthly cramps are far beyond ordinary discomfort and can make normal activities difficult — yet they’re sometimes wrongly considered just part of having periods.

The soreness doesn’t always end with the bleeding. People commonly notice:

• Discomfort during or following intimate moments

• Pain when passing stool or urine, especially around the time of a period

• Ongoing dull or intense tenderness in the pelvic region

When deeper tissues involve the intestines or bladder, additional troubles can include noticeable abdominal swelling, changes in bowel habits, cramps during bowel movements, or stinging when passing urine — issues that are sometimes confused with digestive or urinary disorders.

Further common experiences

• Very heavy or lengthy monthly flow, often with large clots that make everyday tasks harder

• Lasting tiredness that feels overwhelming and isn’t fixed by sleep

• Challenges when trying to become pregnant (though many people still conceive without help)

• Feeling sick or throwing up near the time of a period

• Headaches that seem tied to monthly changes

• Aching in the legs caused by pressure on nerves

• In unusual cases, pain in the upper body or chest area

Impact beyond the body

Living with this condition can affect many areas of life — from studies and work to close relationships and emotional health. The uncertainty and ongoing discomfort can lead to feelings of worry, sadness, or being alone in the struggle.

If these descriptions feel familiar, know that what you’re going through is genuine and matters.

Things worth knowing

• This condition is not cancerous, cannot be passed to others, and is not linked to sexual activity.

• Similar signs can come from other health issues — professional guidance is important.

• Various approaches, including medication for pain, hormonal options, or surgical procedures, can help improve daily life, even if it takes time to discover the best combination.

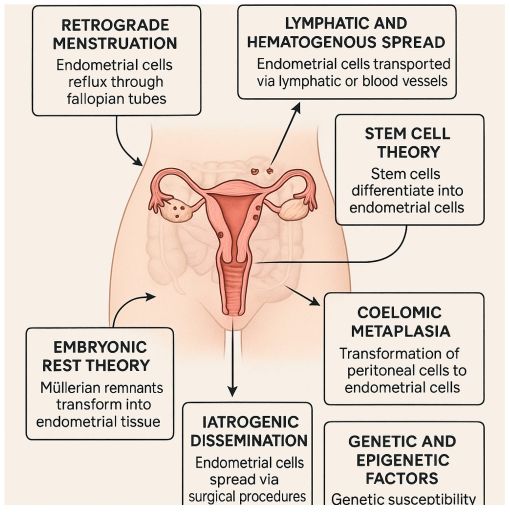

Exploring the Origins of Endometriosis

Researchers still haven't pinpointed a single origin for this condition. Instead, it likely arises from a blend of multiple elements working together, varying from one person to another.

Key to remember: no personal actions or choices trigger this disorder.

Current views highlight its ties to ongoing body-wide swelling and immune responses. Large genetic studies show connections with other issues like migraines, digestive disorders, certain immune-related illnesses, and mood challenges — explaining why effects spread beyond the pelvic region.

This perspective frames the condition as a broader inflammatory process rather than solely a reproductive one.

Backward Flow During Menstruation

A long-standing idea suggests that during monthly bleeding, some tissue fragments move backward through the tubes into the abdominal space. There, they can settle on nearby surfaces and develop further.

This backward movement happens in many who menstruate, but usually the body removes the fragments naturally. In those affected, the fragments may persist and expand due to other influences.

This concept accounts for many typical cases but falls short for rarer ones, such as occurrences before monthly cycles begin, after womb removal, or in exceptional situations involving high hormone exposure.

Other Proposed Pathways

Additional ideas address situations the backward flow alone doesn't cover:

• Cell transformation: Nearby abdominal lining cells might shift into tissue resembling the womb lining, prompted by hormonal or inflammatory signals

• Distant transport: Fragments could move via blood vessels or lymph channels to far-off sites like the lungs or brain

• Early developmental origins: Certain cells might retain the potential to turn into this tissue type from embryonic stages or through migrating stem cells

These pathways help clarify unusual locations and early or non-pelvic appearances.

Role of Inherited Factors

Family history significantly raises likelihood — having a close relative with the condition can increase chances several-fold. Studies reveal gene variations linked to immune activity, swelling responses, hormone processing, and cell attachment.

Hormonal and Immune Contributions

Estrogen drives growth of displaced tissue, promoting its expansion. Often, the balancing hormone (progesterone) loses effectiveness, allowing unchecked buildup.

Immune responses falter: protective cells don't eliminate stray fragments effectively, while others may support their survival. This fosters persistent low-grade swelling, new vessel formation to nourish the tissue, and scarring.

External and Lifestyle Elements

Surroundings can influence vulnerability, including exposure to certain chemicals (like those disrupting hormones), ongoing stress, gut bacteria imbalances, cellular stress, or gene expression shifts. These don't start the condition alone but may intensify it in predisposed individuals.

Why Deeper Insight Helps

Growing evidence connects this disorder to immune and inflammatory pathways, including overlaps with conditions like rheumatoid arthritis. This opens possibilities for therapies targeting these processes directly, beyond hormone-based approaches.

Advancing knowledge brings promise for kinder, more targeted options that address root mechanisms rather than just easing signs.

Understanding the Long Road to Confirmation

One of the most difficult realities for many facing this condition is the extended time needed to reach a clear understanding of what is happening. Studies consistently show an average delay of 7 to 10 years — and sometimes longer — between the onset of noticeable challenges and an official confirmation.

Several factors contribute to this wait:

• Discomfort levels often do not correspond to the extent of tissue spread — mild cases can cause severe aching, while more advanced involvement may produce fewer obvious signs

• Many indicators closely resemble those of other frequent health concerns, such as digestive disturbances, muscular growths in the womb, or pelvic inflammations

• Severe monthly cramps, especially in younger years, are frequently regarded as typical rather than investigated further

• Shallower or smaller growths can be hard to detect without specialized approaches

This prolonged uncertainty can feel isolating and exhausting, but recognizing the pattern helps many advocate more effectively for themselves.

The Step-by-Step Journey Toward Clarity

Reaching confirmation involves a gradual process, starting with conversation and advancing through targeted checks as needed. Each stage builds understanding and helps guide appropriate support.

Detailed Conversation and History Review

The foundation lies in openly sharing your experiences. Healthcare providers typically explore:

• When discomfort first appeared and how it presents (sharp, dull, constant, or cyclical)

• Any worsening around monthly bleeding, intimacy, bowel movements, or urination

• Patterns of flow — heaviness, length, clotting

• Additional changes, such as digestive upset or bladder sensitivity

• Occurrences of similar issues among close family members

• Any difficulties or concerns regarding conception

Maintaining a personal record over several cycles — noting intensity, timing, triggers, and what offers temporary relief — often proves invaluable. This detailed account helps highlight connections that might otherwise go unnoticed.

Careful Pelvic Evaluation

A gentle hands-on assessment allows the provider to check for tenderness, unusual lumps, scarring behind the womb, restricted organ movement, or fluid collections on the ovaries. While helpful clues can emerge, smaller or surface-level tissue changes frequently remain undetectable through touch alone. Therefore, typical results never fully exclude the possibility.

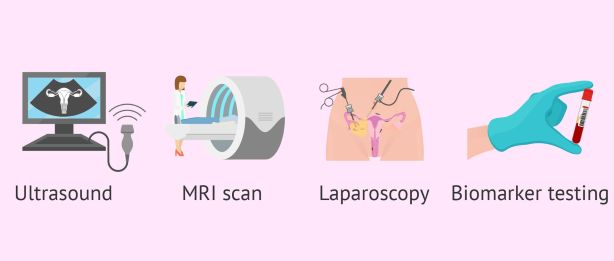

Advanced Imaging Options

Sound-based scanning (ultrasound) provides a safe, non-invasive view inside the body. When conducted vaginally by someone skilled in recognizing related features, it excels at identifying ovarian fluid-filled sacs or deeper tissue involvement. Abdominal placement may also be used for broader perspective.

Magnetic resonance scanning (MRI) creates highly detailed pictures using magnetic fields and waves. It proves particularly useful for mapping exact placements, measuring growths, and preparing for potential interventions — especially when nearby structures like intestines or bladder might be affected.

Both methods help eliminate alternative explanations and outline next steps, though finer surface deposits often escape detection on scans.

Definitive Internal Inspection: Laparoscopy

The most reliable confirmation comes from a carefully planned minor procedure known as laparoscopy. Performed under comfortable relaxation, it involves tiny openings near the navel to insert a slender viewing tool into the abdominal space.

This direct approach allows close examination of pelvic surfaces, assessment of tissue distribution, depth, and characteristics. Small samples can be gathered for laboratory analysis, and — when arranged in advance — visible growths can frequently be treated or removed during the same session, merging verification with immediate relief.

Current practice reserves this step more selectively: when imaging aligns strongly with described experiences or initial supportive measures succeed, proceeding straight to procedural viewing may not be essential.

Methods with Lower Dependability

Standard blood markers, routine scans, or basic internal evaluations cannot independently verify or dismiss the condition. Levels may remain ordinary despite clear tissue presence, or fluctuate due to entirely unrelated causes. Ongoing research explores newer indicators, but none yet replace comprehensive assessment.

Benefits of Specialized Expertise

Seeking providers with focused training in this field often dramatically shortens the pathway. Their deeper familiarity with diverse presentations, skillful interpretation of advanced imaging, and individualized guidance lead to quicker, more precise outcomes.

For adolescents and younger adults, prompt attention holds special value — early support can help limit progression and safeguard long-term well-being and choices.

💛 Vital reminders along the way:

• Your descriptions and feelings deserve serious consideration.

• Persistent advocacy pays off — clarity is achievable.

• A knowledgeable and attentive provider will partner with you fully.

Managing endometriosis varies greatly from person to person. Approaches that bring relief to one individual might not suit another, and finding the right combination often involves exploring multiple paths.

At present, no complete remedy exists for this condition. Available strategies focus on easing discomfort, slowing progression, and enhancing daily well-being. Choices should always involve close collaboration with healthcare providers, taking into account factors like current life stage, symptom intensity, and personal goals.

Easing Discomfort

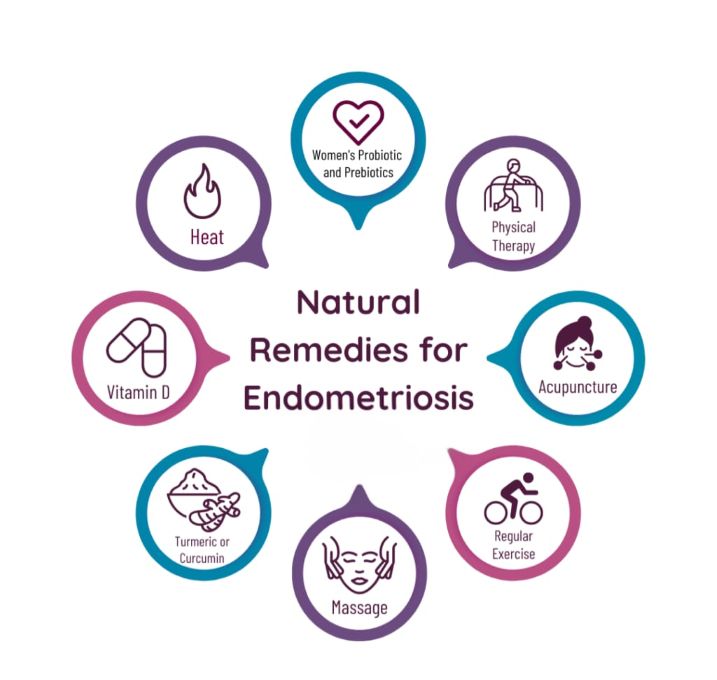

Everyday relief often starts with simple measures:

• Applying warmth, such as a heating pad or warm soak, to soothe aching areas

• Resting in comfortable positions and minimizing tension

• Over-the-counter anti-inflammatory drugs (like ibuprofen) to lessen swelling and cramps — best started early when discomfort is anticipated

• Basic pain relievers (such as paracetamol) for milder issues

More targeted options include:

• Specialized physical therapy to build pelvic strength, improve posture, and release tension

• Devices that deliver gentle electrical pulses (TENS units) to interrupt discomfort signals

• Medications that adjust how the body processes ache signals (often low-dose types originally for other uses)

• Access to dedicated discomfort management centers for comprehensive guidance

Hormonal Approaches

Since growth of misplaced tissue depends on estrogen, many therapies lower or balance this hormone to reduce expansion and ease signs. These are temporary — effects fade once stopped — and they don't remove adhesions or directly boost conception chances.

Common choices include:

• Combined contraceptive methods (pills, patches, or rings) to steady hormone levels

• Progestin-focused options (pills, injections, or intrauterine devices) to thin lining and limit growth

• Advanced agents (like GnRH modulators) that pause ovarian activity, often with add-back low-dose support to counter side effects

Discuss potential benefits, drawbacks, and alternatives thoroughly with a provider.

Surgical Pathways

Procedures can clear visible growths, separate stuck tissues, and drain cysts, often providing notable easing of discomfort.

Main categories include:

• Preserving approaches — typically minimally invasive (keyhole) methods to excise or ablate deposits while keeping reproductive structures intact

• Involved procedures — for deeper spread affecting areas like intestines or urinary system, often needing coordinated specialist input

• Definitive operations — removal of the womb (with or without ovaries) considered only after other paths fail and when family-building is complete; these are permanent and trigger early menopause if ovaries are included

Benefits can be significant, though regrowth is possible, and thorough preparation is essential.

For some women, these treatments bring meaningful relief. For others, benefits may be temporary, incomplete, or come with side effects. Importantly, standard treatments often focus on managing symptoms, rather than addressing the broader inflammatory and immune aspects of the disease.

The most effective approach for many women is multidisciplinary: treating not just the lesions, but the whole person.

And that's the approach that I want to share with all of you: A Whole-Body Approach to Living with Endometriosis

More than symptom control

Traditional treatments often focus on suppressing hormones or managing pain. While these options can help some women, they don’t always address the deeper drivers of endometriosis — such as inflammation, immune imbalance, stress, and nervous system overload.

A holistic approach looks beyond symptom relief and asks:

• What does your body need to feel safer?

• How can inflammation be reduced gently?

• How can the nervous system be supported?

• How can daily life become more manageable and meaningful?

Building your support team

It is very beneficial for women to work with a team that may include:

• A gynecologist or endometriosis specialist

• A pelvic floor physiotherapist

• A nutritionist familiar with anti-inflammatory approaches

• A pain specialist

• A psychologist or therapist

Mental and emotional health support is not optional — it is essential. Living with chronic pain affects mood, identity, relationships, and self-trust. Being supported emotionally is part of healing, not a sign of weakness.

The role of holistic care

Holistic treatment does not mean ignoring medical care. It means integrating tools that support the body and mind together, such as:

• Nourishing, anti-inflammatory food choices

• Gentle, consistent movement that respects pain limits

• Stress regulation and mindfulness practices

• Nervous system support

• Improving gut health and sleep quality

This approach brings something medication alone never did: a sense of peace and control.

Choosing what fits you

Endometriosis treatment is deeply personal. What helps one woman may not help another — and that is okay. Healing is not linear, and progress can be slow. The goal is not perfection, but a life that feels more livable, supported, and aligned with your values.

Ongoing research continues to explore gentler, non-hormonal options that target inflammation and immune pathways directly — offering real hope for the future.

💛 You deserve a life beyond pain.

Carol